Chappies Facts and Township Wisdom

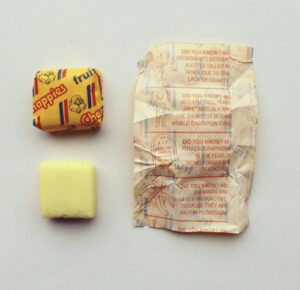

In the shade of a school wall during second break, someone unwraps a piece of Chappies. Not just to chew, but to learn. On the inside of that yellow-and-blue waxy wrapper, there’s a fact printed in tiny ink. Sometimes it’s about giraffes or volcanoes. Sometimes it’s something half-believable like “Your fingernails grow faster on your dominant hand.” It doesn’t matter what it says, really. The point is, it’s there. Something to read. Something unexpected. Something that sparks. The kids gather around whoever’s got the gum, and someone reads the Chappies fact out loud, like it’s a secret passed down.

For some children, it’s the first time they hear the word “constellation” or learn that crocodiles can’t stick out their tongues. The facts aren’t always true, or useful, or complete. But they’re part of a larger kind of learning. One that lives outside the classroom, in the margins of township life. Chappies gum, with its noisy pop and its stubborn chew, is one of the many small teachers that roam freely through the streets, the spaza shops, the lunch queues.

Education, where we come from, has always had unofficial branches. You learn how to read a room before you learn to read a book. You learn how to greet properly before you learn algebra. You learn how to count change, how to stretch airtime, how to tell if someone’s hungry even when they say they’re not. These lessons don’t come in textbooks. They come from watching your cousins, from listening to grownups argue about politics around the braai, from eavesdropping on your neighbour’s radio when the kitchen door is open.

Township wisdom doesn’t announce itself. It sneaks in through conversation. Through sayings repeated until they sound like law. “Don’t borrow salt at night.” “If the dog barks at nothing, go check on your aunt.” “Don’t sweep someone’s feet or they’ll never get married.” These things don’t make it onto exams, but they live in our bodies. They guide how we move. They tell us when to speak and when to hush.

You learn from your older sibling’s report cards. From their scars. From the shoes they wore until they had holes. You learn the value of silence when there’s shouting in the next room. You learn that a nod can mean yes, no, or “let’s not talk about this now.” You learn the rhythm of disappointment, the choreography of pretending things are fine when the electricity’s off and the bread is finished.

There are rules about when to run and when to walk. About which streets feel safe, not by design, but by memory. There’s an education in looking. You learn to tell who’s struggling by the way they open their lunchbox. You learn to spot a borrowed school jersey. You learn that sometimes, people disappear without explanation, and the polite thing is not to ask too loudly.

Teachers in class might drill you on BODMAS and isiZulu comprehension, but your real test comes when you get sent to the shop with R20 and have to come back with everything your mother asked for, including change, and a proper receipt. You learn to argue with taxi drivers, to negotiate your space, to carry yourself taller even when your voice still squeaks. You learn from the guy on the corner who sells pirated DVDs and knows more about current affairs than anyone on the news. You learn from the gogo who plays number games with the Lotto tickets, says they come to her in dreams.

And then there’s the Spaza. The one with a fridge that buzzes louder than the generator. That place is a school too. You learn how to wait, how to respect the queue even when it doesn’t look like a queue. You learn how to greet in a way that gets you served faster. You learn that some prices are fixed, but others bend depending on how well your uncle knows the owner. You learn that credit is a trust exercise, and not everyone passes.

And then there’s the Spaza. The one with a fridge that buzzes louder than the generator. That place is a school too. You learn how to wait, how to respect the queue even when it doesn’t look like a queue. You learn how to greet in a way that gets you served faster. You learn that some prices are fixed, but others bend depending on how well your uncle knows the owner. You learn that credit is a trust exercise, and not everyone passes.

Sometimes, knowledge isn’t just about gaining something new, but about holding onto what’s at risk of being lost. Like the way to make amagwinya rise without measuring anything. Like how to use newspaper as a tablecloth when guests arrive unexpectedly. Like the sound of your grandmother’s stories, how they change depending on the mood, but always carry a warning wrapped in humour.

The school bell may ring at 2, 30, but the real learning often starts after that. On the walk home. At the shebeen where uncles speak louder as the sky darkens. At the tuck shop where the older girls talk about life in metaphors you won’t understand for another five years. At the field where boys argue tactics using beer caps and call it “strategy.”

Every township child has a double education. The one that gets graded, and the one that gets lived. The latter doesn’t come with certificates, but it gives you fluency in the language of survival. It teaches you how to fail and still laugh. How to expect little and give much. How to hold multiple truths, joy and pain, hunger and celebration, in the same afternoon.

The wrapper from a Chappies doesn’t last long. It gets thrown away or stuck behind someone’s ear for safekeeping. But the habit of looking for a fact, for something to know and pass on, that sticks. Long after the gum has lost its flavour, the search for knowledge remains. It becomes part of how we see the world, curiously, creatively, hungrily.

And maybe that’s the point. That learning doesn’t always come from the top down. Sometimes it comes in chewable, tearable, strangely sweet pieces. Sometimes it comes in whispers on the stoep. Sometimes it’s wrapped in humour, or hardship, or a half-true story from someone who’s seen too much. But it’s there. Always there. In the way we talk. In the way we remember. In the facts we carry long after school is out.